Food counterfeiting and the long history of food fraud

In this article, we address the sensitive topic of food fraud, which most people probably only know from the media and which may be closer to you than you think.Unfortunately, food fraud in the form of food counterfeiting is a sad part of the food industry, and not just in modern times.

Food fraud is as old as civilization itself. In ancient Babylon, around 3,700 years ago, it was already mentioned and criminalized in one of the oldest legal texts in the world, the Code of the ruler Hammurabi.

Although we can no longer fully comprehend the extent of food fraud at that time, it is clear that it must have existed, otherwise no laws would have been passed against it.

One of the first and actually traceable types, as it is explicitly mentioned in the legal text, must have been the distribution of insufficient quantities of beer, other translations also speak of wine, in relation to the payment. The law also explicitly mentions the stretching or panning of beer.

Section 108 of the Code of Hammurabi states:

"Suppose a beerskin has not accepted grain as payment for the beer, has accepted money by weight, and (or) has made the value of the beer less in proportion to the value of the grain, then that beerskin shall be convicted and thrown into the water."

"Reducing the value of the beer" refers to diluting it with water, which was not only a problem at the time because the customer did not get what he paid for - beer, like bread, was a staple food - but also because this regulation was about food safety, as water was not always edible and could be a potentially unsafe food.

Cuneiform writing - a tool for documenting goods

The Codex Hammurabi was written down in the so-called cuneiform script. This is remarkable because cuneiform was originally a purely administrative tool that was primarily used in business, religion and taxation.

Since a large part of the economy at the time was based on agriculture, trade was naturally also based to a not inconsiderable extent on the buying and selling of food.

In order to catalog these, a clay tablet was carried along with the traded goods, into which wedge-shaped marks were pressed into the still soft clay with the help of a wooden stylus.

In this way, it was possible to trace which goods and quantities were available. A kind of early register that also made it possible to trace the flow of goods.

Of course, this documentation was by no means forgery-proof.

Regulations similar to the Code of Hammmurabi, which were intended to ensure food safety and prevent fraud, were later also written down in Hebrew scriptures, which were later adapted by Christians in the Old Testament.

Leviticus 7:24 states:

'The fat of a dead or torn animal may be used for any purpose, but you must not eat it under any circumstances.'

Although it was not yet known at the time that bacteria were behind putrefaction processes, the fact that rotten meat was known to cause disease can still be deduced from this passage.

Furthermore, Deuteronomy, chapter 25 13-15

'13: You shall not have two different weights in your bag, one larger and one smaller.

14: You shall not have in your house two different ephahs (hollow measures for grain), one larger and one smaller.'

Here, too, the intention was to put a stop to food fraud.

Food fraud in ancient China

Of course, there were also cases of food fraud and attempts to take effective countermeasures in other parts of the world.In China, for example, there are reports from the Zhou dynasty(1046-256 BC) that deal with regulations and measures against food fraud.

Various regulations were reproduced in the so-called'Book of Rites', e.g. that it was forbidden to sell unripe fruit on the market.

Compliance with these regulations was of course also monitored. For example, there were employees at the markets who were specially designated to prevent the production of counterfeit products and the deception of buyers.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), food that could cause poisoning was burned and traders caught with such products faced severe punishments. These punishments ranged from lashes and banishment to the death penalty if the victim died of food poisoning. Later, during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911), deaths caused by food were equated with murder and manslaughter

You can find out more about China's dynasties in the following ZDF documentary.

Sweet poison in sweet wine in ancient Rome

However, the best documented cases of food poisoning or food adulteration in antiquity probably originate from ancient Rome.A particularly serious issue here is one that not only lasted for centuries, but even for millennia, had its origins in ancient Greece and was cultivated by the Romans to a disastrous level.

This was a case of ongoing lead poisoning from wines and wine-based drinks.

Curiously, this even had its origins in the idea of food safety.

Water was often an unsafe product at the time, as unlike today, there were no sewage treatment plants or water purification systems. Water taken from rivers or lakes was often contaminated with bacteria, as wastewater was simply discharged into them. If fresh spring water was not available, it was therefore not advisable to drink water.

This was usually remedied by wine, which, due to its alcoholic fermentation, could generally be drunk without any problems and without the consumer contracting acute food poisoning.

Today, of course, we are aware of the negative consequences of long-term alcohol consumption, but alcohol was generally not the only poison contained in Roman wines.

It is known that over 4,000 years ago, must was boiled in lead pots to reduce it and produce a sugar syrup. This was produced in various stages of reduction. Carenum, which corresponded to 2/3 of the original volume. Defrutum corresponded to half of the original volume and sapa made up only a third.

However, the concentrated end product sapa was not only incredibly sweet due to the naturally contained fructose, but also contained another sugary-tasting ingredient due to the production process, the carcinogenic and neurotoxic lead(II) acetate, which was formed in the lead pot during the boiling process.

The resulting sapa was sometimes used to sweeten food. However, its main purpose was to sweeten and additionally preserve wines.

sapa was probably used extensively, especially by the wealthier sections of the population, which naturally led to gradual lead poisoning with the corresponding symptoms.

Although lead was suspected of being poisonous in both Greece and Rome, its use continued unabated, in some cases until the 18th century.

The first bans on sapa were issued in Spain and France in the 15th century.

Other cases of lead poisoning from drinks occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries. In England, lead-contaminated wine and cider (the so-called Devonshire colic) and in the North American colonies due to lead-contaminated rum, whereas the Massachusetts Bay Colony issued an ordinance in 1723 that was intended to ensure food safety and prohibited the distillation of rum or other high-proof alcoholic beverages in lead-containing vessels or pipes.

In ancient Rome, however, there were not only unintentional cases of unwanted additives in wine. Wine was obviously blended on a grand scale at the time with the intention of maximizing profits.

This is evidenced by reports from Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar who, in his 37-volume encyclopaedia "Naturalis historia", reports on the means by which wines were altered.

One of the volumes states:

"The customs of the time are such that only the name of a vintage is sold, while the wines are adulterated the moment they enter the vat."

He goes on to describe the many ways in which the wine of the time was adulterated.

The simplest blending method was, of course, dilution with water, which is said to have taken place at a ratio of up to 20:1 in some cases.

But apparently not only spring water but even seawater was used for dilution, although this would certainly have been quickly noticed due to the taste.

However, Pliny was probably particularly displeased with wines from Gaul, as these probably underwent large-scale colour and aroma changes, especially through the use of herbs. This can be read in'A history of the adulteration of food before 1906' by F. Leslie Hart

Ripe grapes - shortly before harvest

So even in ancient times there were cases of fraudulent labelling, gross falsification of food and cases of consumer danger due to improper handling of food.

Of course, such incidents of food fraud were not limited to those times, but became more diverse over time, also due to changes in eating habits and better technical aids.

The Middle Ages - as bad as its reputation?

In the early Middle Ages following antiquity, conditions did not get better, but in many cases probably worse, which was unfortunately also due to the increasing specialization of trades and created new opportunities for food fraud.In Europe, for example, the milling and baking trades became increasingly popular. While the original diet of the population in the 10th century, for example, still consisted primarily of cereal porridges that could be prepared at home, this was of course not so easy with bread.

This required a suitable milling tool for the production of fine flour, which of course also had to be baked afterwards.

Both were laborious for the average population and only possible with simple means, as both brick bread ovens and mills had not yet become widespread for cost reasons. Grain was therefore usually crushed with mortars and the resulting coarse flour was baked in the form of flat cakes in clay pots on open coals. Sourdough breads or breads baked in the form of a loaf were rather unknown at this time and had also not yet become established.

This changed by the 13th century, as by then both brick bread ovens and mills had become widespread. Initially, it was mainly monks in monasteries who had such ovens at their disposal and who practised the milling trade. Village communities also sometimes shared an oven or a mill, which usually belonged to a landlord and were also subject to the so-called mill obligation.

This means that farmers were only allowed to have their grain ground in a specific mill and had to pay the miller for this in the form of money or grain, who in turn had to pay rent to the landlord.

The historical example of the Aspermühle mill illustrates this very well, as it too was originally attached to the nearby Graefenthal monastery and was originally only allowed to grind for its inhabitants. This can be read in more detail in our article on the history of the Aspermühle.

Aspermühle around 1920

The outsourcing of flour production and bread making naturally increased the risk of food fraud and, unfortunately, millers had a less good reputation for a long time. While nowadays mills are generally associated with honest craftsmanship and high-quality, healthy food, millers at that time were often accused of all sorts of disreputable things.

However, the relationship with millers was clearly ambivalent, as millers were absolutely indispensable members of society as they ensured the food supply. Without flour, which formed the basis for the proverbial daily bread, famine would have quickly struck the population. The miller therefore naturally had special rights. On the one hand, the miller was not subject to the law on public holidays, which in turn was considered unchristian, and on the other hand, and much more importantly, a miller did not have to, or rather was not allowed to, go to war.

However, this was not only an advantage, as he was denied the honor of bearing arms, which made him dishonest in the eyes of the population.

This went hand in hand with the fact that millers in the Middle Ages were not considered fit for the guilds and provided the executioners, who were also considered dishonest and guildless, with the gallows ladders. This only ended with the Imperial Police Regulations of 1548 and 1577, when millers were declared fit for the guild and therefore honest.

For the reasons described above, millers did not have an easy time of it in society. But that was not all. As mills were often located exclusively outside the village, as they either needed an exposed , windy location or a location directly on the river to operate, their operators, the millers, were of course also often outside the village community. This led to all kinds of rumors about the mill operators in the superstitious and poorly educated society of the Middle Ages.

One of the most prominent and persistent rumors was probably that the millers diverted some of the delivered grist.

This makes sense because, on the one hand, the miller was of course entitled to a wage of one sixteenth per bushel ground.

On the other hand, the miller was liable to pay rent and also had to collect tithes for the sovereign who owned the mill, which were also deducted from the delivered goods.

In order to be able to determine the correct amounts, it was of course necessary to be able to calculate, which was certainly not commonplace in medieval estates society, as education was reserved for the clergy and nobility.

This situation naturally offered all kinds of scope for speculation as to whether the quantities billed corresponded to the quantities the miller was entitled to and, of course, this also offered the miller scope for fraud, as his customers could not necessarily check it.

Old windmill in the Riga Open-Air Museum

Georg Paul Hönn's fraud encyclopaedia, published in 1721, lists alleged cases of fraud.

He lists that millers are said to have used different measures. A larger measure to record the incoming quantities and a smaller measure for the outgoing quantities.

He also states that millers kept hidden bags and boxes with double bottoms in which they hid stolen flour.

Millers are also said to have fed their livestock with other people's grain.

What exactly and to what extent such practices were actually based on reality has unfortunately not been handed down and much of it can probably be classified as hearsay, because the more sensational a story is, the better it sells. That was certainly even more true back then than it is today.

However, the fact that some millers may have been dishonest is proven by the mill regulations published in 1804, in which the basic rules for millers were written down.

Among other things, these rules regulated the weights and measures that a miller had to use, the grinding fee that he was allowed to take from his customers and also how he had to behave towards his customers. The last point included, among other things, that no cattle were allowed to be present in the mill so that no grain was eaten, that customers were allowed to stay in the mill until the end of the grinding process and that the mills were to be kept clean and tidy.

These regulations certainly also contributed to the fact that the image of the miller and mills in general has changed greatly for the better today and mills are often seen as the epitome of healthy eating.

Another grain-based product which, as already described, was already widely known and consumed at the time and which is now associated with what is probably the best-known food law in the world is, of course, beer.

Beer as a staple food - widespread widespread but also healthy?

However, this was probably not comparable to beer as we know it today. There were many reasons for this.Germany, as we know it today, did not yet exist; rather, the territory of Germany today was part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and probably comprised a maximum of around 300 sovereign states with their own legislation.

This alone makes it clear that uniform food legislation was unthinkable. The following ZDF documentary provides a summary of the history of beer brewing.

Initially, there was no legal basis for brewing beer and certainly no standardized purity law as we know it today. As a result, beer, which was considered a staple food, contained many different ingredients that seem rather strange today.

The mixture of herbs known as "Grut" varied depending on the region and contained, for example, gale, yarrow, caraway, juniper or spruce tips to give the beer a characteristic taste. These beer blends were widespread and popular.

However, the mixtures often contained not only flavor-altering additives, but also ingredients that had a significant impact on people's health and psyche.

For example, deadly nightshade, opium poppy, wormwood, marsh sorrel and other psychoactive or poisonous substances were used by medieval brewers. The medieval brewers added psychoactive or poisonous substances to enhance the effect of the beer.

Chalk or soot were also used to change the color or taste.

The consequences for consumers of these additives were probably less pleasant.

The Purity Law - consumer protection or clever marketing?

It was therefore essential to enact regulations for the production of beer and the first purity laws gradually became established in the small states.One of the first cities to regulate the art of brewing was Augsburg in the middle of the 12th century, followed by Nuremberg at the beginning of the 14th century. Over the course of the century, other cities such as Weimar and Munich followed suit.

However, this was not only based on the protection of health, but also had tangible economic aspects, as some of the herbs used in the Grut mixtures were not available in Bavaria and purity laws were therefore of course absolutely beneficial for advertising.

In addition, the 14th century saw the beginning of the so-called Little Ice Age, which saw the introduction of the first purity laws. In the 14th century, the so-called Little Ice Age began, which caused problems for agriculture, which had been relatively stable until then, and led to poor harvests and hunger.

As wheat and rye were considered to be of higher quality and were mainly used for baking bread, and to prevent famine, only barley was to be used for brewing beer.

The Bavarian dukes William IV and Louis X had a clear idea of this, issued in 1516, which is regarded as the forerunner of the Bavarian Purity Law of 1918, also had the state coffers in mind, because where previously all kinds of ingredients were used in beer, now only barley was allowed to be used and this was ultimately subject to tax. The barley juice brewed in accordance with the new purity law therefore filled the state coffers to no small extent.

Belgian beer - not brewed in accordance with the purity law, but certainly delicious.

While the quality problems with beer were at least halfway solved in the following centuries, this was unfortunately not usually the case with most other foods.

Death from the cooking pot - food counterfeiters without scruples

One of the first truly documented works on food adulteration was the book "A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons" by the German chemist Friedrich Accum, published in London in 1820. The German translation "Von der Verfälschung der Nahrungsmittel und von den Küchengiften" was published in Germany a year later.In this book, Accum not only listed the foods that were adulterated, but also indicated how this was done, how harmful the individual foods were to health and how the adulterations could be recognized.

The methods he used to detect food adulteration ranged from microscopic examinations and measuring physical properties such as density and color to chemical examination methods.

Accum also paid particular attention to the adulteration of flour and bread. His book contains instructions on how to decompose bread with the help of potassium chlorate and then use various other chemical means to investigate whether sulphuric acid, alum or potash had been added to the original bread dough.

Alum in particular was added to bread in many ways during the Victorian era to optimize the appearance of the dough and to ensure that it contained more water.

As alum also contains aluminium, it is easy to imagine that this was not conducive to good health.

Of course, it was not only bread that was adulterated. He also reports of a woman who became ill from eating cucumbers dyed with copper sulphate and eventually died.

Apparently, cinnabar, which chemically represents mercury sulphide, and red lead, an anti-rust paint consisting of lead(II,IV) oxide, were often used to dye cheese.

These are two highly toxic substances that have no place in food and yet were unscrupulously used to deceive consumers.

These reports were also confirmed by other authors and dealt with in even greater detail.

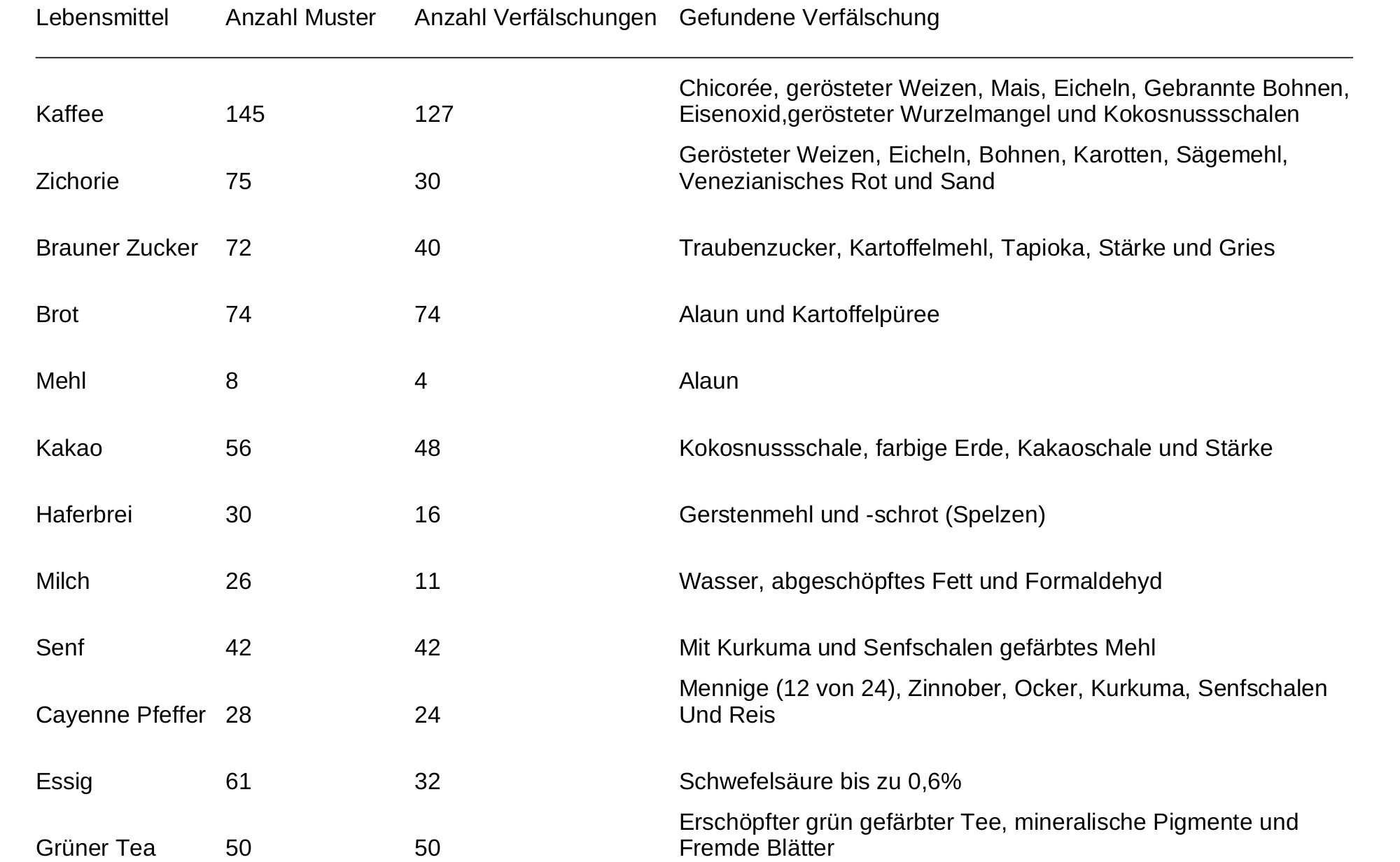

For example, between 1851-1854, the chemist Arthur Hill Hassall published a series of articles in the medical journal "The Lancet", which still exists today, which finally led to the book "Food and Its Adulterations" in 1855, in which he lists a whole range of staple foods that he had examined and which were subject to adulteration

As can be seen from the following table, which summarizes the adulterations found, food adulteration was commonplace and consumers were generally unable to avoid it.

This table is based on 'Food and its adulterants', where the second column shows the number of samples taken across London, the third column shows the number of samples that tested positive for one or more adulterants, and the fourth column shows the type of adulterants found.

For example, all bread samples tested were spiked with alum, all green teas tested were spiked with leaves from foreign plants and pigments, and all mustard samples were spiked with turmeric and pods from mustard seeds.

Much of the coffee and cocoa was spiked with soil, starch, roasted wheat, roasted chicory root(Muckefuck), roasted acorn flour and many other additives. Older readers may remember Muckefuck.

Milk, porridge and other foods were also diligently adulterated.

These and other investigations finally led to the British Parliament passing the "Food and Drugs Act" in 1860, which initially only provided half-hearted relief and was therefore tightened up in 1862 and 1872, which ultimately led to 1,500 convictions by 1875. In addition, the previous law wasreplaced in 1875 by theSale of Food and Drugs Act.

Unfortunately, the other European countries and the USA were in no way inferior to the situation in Great Britain, because here too, counterfeiting and forgery were practised for all they were worth.

One very significant case, the so-called'Swill milk scandal', occurred in New York State in the 1850s. Here, various brewers and distillers wanted to take advantage of the fact that the grain used to produce alcohol still had nutritional value and built dairy farms in the immediate vicinity of their production facilities, where cows were kept in city stables without access to open air and daylight and fed on fermentation residues. (see video below)

The resulting milk was of such poor quality and was also laced with gypsum and other additives that it caused high rates of diarrhea in infants and ultimately led to the deaths of around 8,000 children.

The conditions on the food market were therefore rather gruesome and real consumer protection was still miles away.

Food fraud and food counterfeiting in the modern age

But what is the situation today and what can consumers expect from consumer protection and food quality?The first thing you would assume at this point is that there is now a uniform definition in the EU of what constitutes food fraud.

But far from it. The following sentence can be found on the EU Commission's own website.

"EU legislation does not contain a definition of fraud in the food chain."

Instead, there are the following 4 conditions that must be met in order to be considered fraud:

Breach of EU rules: Breach of one or more provisions of EU food chain legislation in accordance with Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/625.

- Deception of customers: Any form of deception of customers/consumers (for example: altered coloring or altered labels that hide the true quality or, in the worst case, even the nature of a product). In addition, the misleading element may also pose a risk to public health as some of the true characteristics of the product are hidden (e.g. undeclared allergens).

- Undue advantage: the deceptive act provides a direct or indirect economic advantage to the perpetrator.

- Intent: examined when a number of factors provide good reasons to believe that certain infringements are not accidental, such as the deliberate substitution of a high-value ingredient with a low-value ingredient, rather than accidental contamination due to the production process.

Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/625 then lists the areas in which an infringement would have to be committed intentionally.

These include food safety, feed safety, genetically modified organisms, animal health and welfare, use of pesticides, production and labelling of organic food and protected geographical indications.

This is, of course, somewhat vague at first. The website of the "Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety" provides a few specific examples in this regard, as can be seen in the following graphic.

Graphic from the Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety

It is easy to see from this that the subject matter is very complex and extensive and difficult for the authorities to monitor.

It is therefore not surprising that the EU has repeatedly attracted attention in recent years due to food scandals.

Most consumers will certainly remember cases such as dioxin in eggs, horsemeat in lasagne, legionella in brewery waste water, contaminated sausage or the Ehec outbreak caused by fenugreek sprouts. Of course, these were by no means the only incidents and certainly not the last.

Some consequences have already been drawn from these incidents in the EU and the member states.

Even before the scandals, the EuropeanRapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) was set up, which serves to ensure a rapid exchange of information and consumer transparency. The database is publicly accessible and can of course also be viewed by consumers.

Here they can get an idea of past and current food problems

Furthermore, the EU Agri-Food Fraud Network was set up in 2013, for example, which serves to collect and exchange information across borders in cooperation with the EC Knowledge Centre for Food Fraud and Quality, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) and the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) and thus uncover food fraud

The FFN also publishes monthly and annual newsletters that report on the unit's work, findings and progress.

Specifically in Germany, the "National Reference Center for Authentic Food", which is based at the Max Rubner Institute, the Federal Research Institute for Nutrition and Food, has also been established.

Its tasks and competencies consist of collecting and passing on specialist knowledge, building up a database with analysis results from authentic reference samples and calibrating analysis methods and, as a result, checking food authenticity in terms of its origin, the production process, the ingredients and the animal/plant species and varieties specified.

These measures are definitely a step in the right direction, but an exchange of information can only take place with information that has already been collected, for which the necessary personnel are needed and this is exactly what is still lacking years after all the scandals.

There is a nationwide shortage of at least 1,500 food inspectors and one inspector is responsible for around 400 companies. As this also includes large businesses where inspections take longer, it is easy to calculate that most businesses can only be inspected once a year at most and many planned inspections are not carried out at all. In some cases, failure rates reach up to 80 percent,

It is therefore not surprising that there is still a high rate of hygiene-related deficiencies and, unfortunately, adulteration.

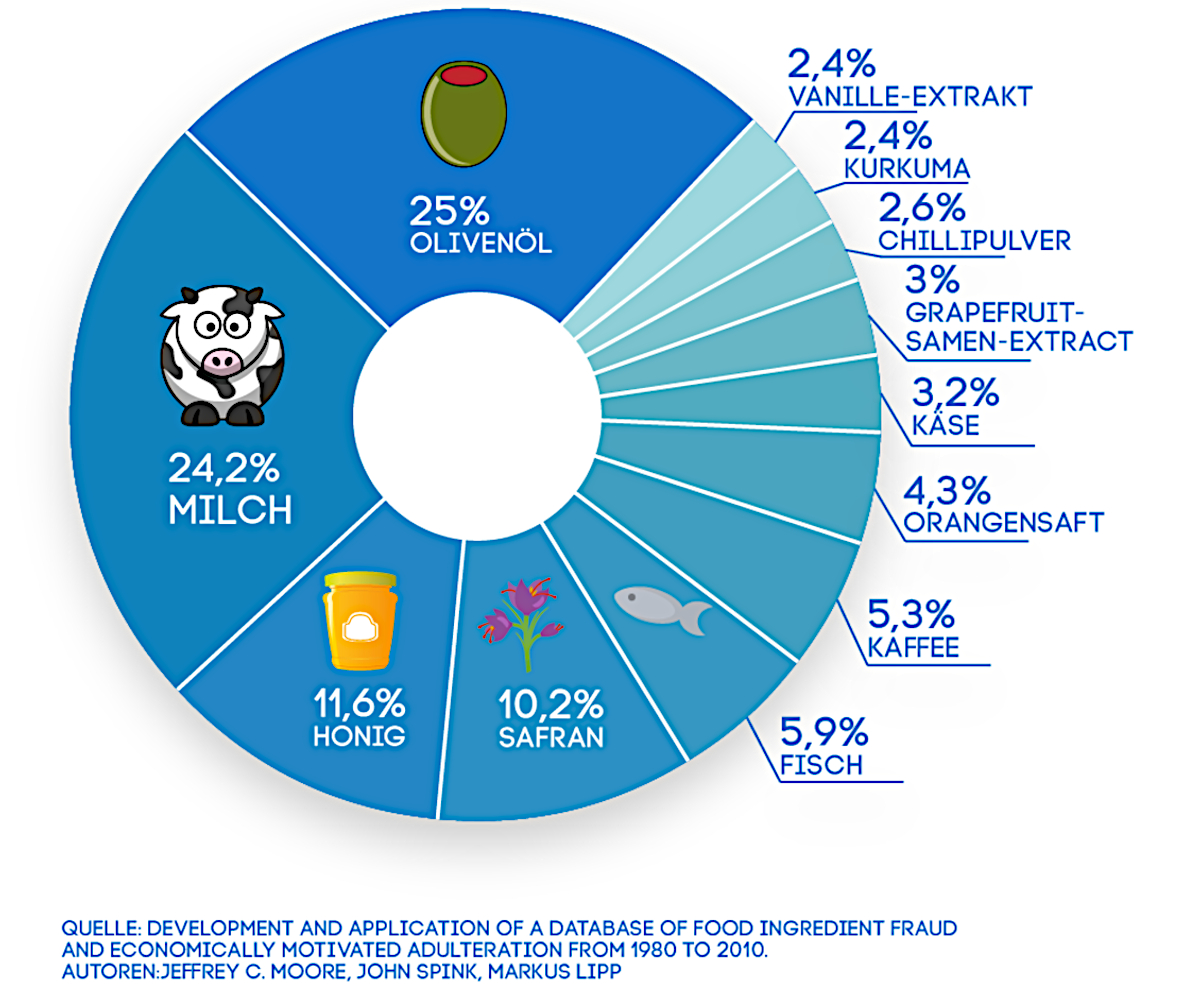

The following graphic shows once again which foods are particularly prone to adulteration.

We will therefore take a closer look at two of these, honey and olive oil.

We will start with the current problem child, which is particularly close to our hearts and which has made sad headlines across Europe in 2024: honey.

The German Honey Ordinance defines honey as follows:

Honey is the naturally sweet substance produced by honeybees by taking nectar from plants or secretions from living parts of plants or excretions from insects that suck on plants, converting them by combining them with their own specific substances, storing them, dehydrating them and storing and maturing them in the honeycombs of the beehive. Honey essentially consists of various types of sugar, in particular fructose and glucose, as well as organic acids, enzymes and solid particles absorbed during nectar collection. The color of honey ranges from almost colorless to dark brown. It can be liquid, viscous or partially or completely crystalline. The differences in taste and aroma are determined by the respective botanical origin.

On the one hand, this states what honey is and at the same time already determines what may no longer be declared as honey.

However, this is also listed again later in the Honey Ordinance.

General requirements

No substances other than honey may be added to honey.

Honey must, as far as possible, be free from organic and inorganic substances foreign to honey. However, neither pollen nor other substances inherent in honey may be removed, unless this is unavoidable when removing inorganic or organic substances foreign to honey. By way of derogation, pollen may have been removed from filtered honey.

Honey must not contain any artificially modified acidity. With the exception of baker's honey, honey must not have a foreign taste or smell, must not have undergone fermentation or fermentation or have been heated to such an extent that the enzymes have been significantly or completely inactivated.

So far so simple. It is actually clearly formulated what honey is or is not and which processing steps may or may not take place.

So why does honey keep making negative headlines?

The answer is very simple. The honey trade is a market worth billions. Every year, 250,000 tons are produced in the EU alone and an additional 200,000 tons are imported.

While the export price for honey averaged 5.69 euros/kg in 2016, the import price was only 2.23 euros/kg and fell significantly to below 2 euros/kg by 2024, to as low as 1.20 euros/kg for Chinese honey.

This naturally tempts many retailers to mix their honey with cheap imports. If the retailer declares this properly, it is easy to recognize this on the label, as it states "mixture of honey from EU and non-EU countries".

This is of course very unpleasant for local beekeepers, as a local beekeeper who produces quality honey can simply no longer keep up with these prices. So while this practice is at least legal for the time being, the consequences for the domestic honey market are of course catastrophic.

The following report shows just how problematic this can be for domestic beekeepers.

But let's stick directly to the keyword legal. Because what the report also addresses is that cheap imported honey is not only so cheap because wages in the countries of origin are significantly lower, but also because the honey is either diluted with cheap substitutes such as glucose or fructose syrup or even completely replaced by such products. The often unsuspecting consumers usually do not notice this, as they simply lack the necessary specialist knowledge.

This is where the food control authorities would actually come into play again, whose job it would be to uncover such machinations. However, as already stated, they are chronically understaffed and therefore rarely in a position to uncover such problems.

In our store you will find pure, unadulterated honey that comes exclusively from friendly beekeepers in Europe:

So it's no surprise that honey keeps making headlines. In 2014, this led to the EU having to amend its Honey Directive, which has been in place since 2001.However, this obviously did not have the desired effect, as various media outlets unanimously reported that the laboratory of the Joint Research Center (JRC) had 320 honey samples analyzed on behalf of the EU Commission in 2021/22, 46% of which were classified as suspicious, in other words, stretched.

The issue was taken up by the Lower Saxony Consumer Center, the Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Austrian Beekeepers' Association, among others.

This resulted in a further tightening of the rules in 2023. In future, the country of origin of the honey must be stated and, in the case of mixed honeys, the percentage from which country.

As this regulation has a transitional period, the EU member states do not have to transpose it into national law until the end of 2025. It will then only come into force on June 14, 2026.

In the meantime, consumers will of course remain in the dark as to which honey they are buying in the supermarket and whether it is honey at all.

It must also be said that an indication of origin in no way protects against adulteration and therefore the latest headlines in this regard date from 2024.

We would like to take a closer look at these at this point.

The German Professional and Commercial Beekeepers' Association and the European Professional Beekeepers' Association have gone and had honey samples from German supermarkets analyzed using a DNA analysis that has not been used for honey for years in the criminological field. The analysis was carried out in the Estonian laboratory Celvia.

The result was expected, but nevertheless shocking and revealed that around 80% of the honey samples tested were falsified.

The beekeepers were accompanied by the ZDF television team from "Frontal". You can find the report in the following video.

Unfortunately, there are many ways to adulterate honey or offer it in inferior quality in order to increase profits.

These are the most common methods:

1. Harvesting unripe honey.

Before the honey can be removed from the hive, it must have undergone a process. The honey does not arrive in the hive as a finished product, but is collected by the bees in the form of nectar, which is then mixed with enzymes and dried by the bees, because a low water content and a high sugar content at the same time serve to preserve it.

If the honey is removed from the hive too early in order to increase the yield, it naturally contains too much water, which makes the honey susceptible to fermentation.

The honey regulation regulates that honey may only contain 20% water. The only 2 exceptions are heather honey with 23% and baker's honey with 25%.

2. Another method would be to feed the bees with sugar during the harvest. This method is chosen because it is of course difficult to prove, as the bees bring in the sugar syrup just like nectar, nectar and sugar syrup are mixed and this mixture is also mixed with enzymes and dried by the bees.

3A third and probably currently the most common method is the addition of fructose or glucose syrup to honey.

These are usually obtained from wheat, potatoes or maize and are not normally detected by conventional analysis methods, as honey also consists to a large extent of glucose or fructose.

This is where DNA analysis comes in, because it analyzes all the components of honey, including the different types of pollen, but also bacteria or viruses that can be found in the beehive.

This allows you to quickly identify whether it is honey at all, or just syrup, for example, or whether the composition of the pollen profile corresponds to what you would expect from honey.

If, for example, the pollen profile is very homogeneous and contains wheat pollen, for example, it is certainly stretched, as bees do not fly to cereals, but the pollen is probably contained in glucose syrup obtained from wheat.

Similar investigations were also carried out in Austria and Switzerland after the results from Germany became known and came to a comparable conclusion, namely that the honeys examined were probably mainly stretched with cheap fructose syrups, as you can see in the following two videos.

For European beekeepers, however, it is not only unpleasant, but a pure catastrophe, because their livelihood is at stake here. How is a beekeeper supposed to be competitive if you can get cheap "honey" for 2 euros a jar in the supermarket?

It must be obvious to everyone that this can only be a counterfeit product.

However, olive oil, not honey, tops the list of counterfeit foods in the EU.

Olive oil - food counterfeiting and mafia business models

Just like honey, olive oil has a distinct history of adulteration and just like honey, it is unfortunately relatively easy to do so. In the case of olive oil, other cheap oils, such as rapeseed or sunflower oil, are generally used for this purpose. At least these are not harmful to consumers. However, olive oil is also produced using lampante oil, which is actually not fit for consumption and is nothing other than lamp oil, i.e. in the past it was just good enough to be used as fuel. But here we are just at the beginning of a series of variable adulterations.One of the biggest and most serious cases dates back to the 1980s. At that time, 38 companies were taken to court in Spain for importing 750,000 liters of denatured rapeseed oil intended for industrial use, mixing it with olive oil and then selling it as food. As the denaturation was carried out with aniline, which is highly toxic, the consequences were unfortunately dramatic.

At the beginning of the trial, 700 of the more than 20,000 people who suffered serious poisoning had already died. Many of those affected suffered from cramps, breathing difficulties and were later confined to crutches and wheelchairs.

Although consumer protection was increased in the wake of the scandal, the judicial penalties were relatively mild.

Olive grove in Croatia

Unfortunately, this was just one of many incidents that were to follow in the years to come, although not all of them ended so dramatically.

2011 a case became known in Italy in which the considerable price differences between the various countries of origin of olive oil were exploited.

The most expensive olive oil by far comes from Italy. It sometimes costs 10-20 times the price of olive oil from Spain or Tunisia, for example. This naturally arouses desires and so large quantities of olive oil are imported to Italy from these countries every year and exported throughout the EU as Italian olive oil. As with honey, it is estimated that around 80% of total production is affected.

But that is not all, as this oil often has considerable defects in the form of mold contamination. Around 50% of the olive oils tested in Italy in 2011 were simply moldy. Although this does not necessarily pose a risk to consumers, there are types of mold that produce aflatoxins, i.e. mold toxins, which are highly toxic and carcinogenic.

While concealing the indication of origin does not necessarily have to be bad for the consumer, apart from the monetary disadvantage, because the quality of the olive oil can theoretically still be good, this was unfortunately no longer the case in the next example.

In 2019, a mixture of 150,000 liters of sunflower and soybean oil mixed with chlorophyll and beta-carotene was confiscated.

The 24 people arrested in Italy and Germany had sold this mixture to restaurants and stores in Germany and Italy as extra virgin olive oil, i.e. olive oil of the highest quality, which must be cold-pressed, have a flawless smell and taste, low acidity and, of course, be unadulterated.

Unfortunately, this had nothing to do with good olive oil.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case either, and in 2024 another 42,000 kg of counterfeit "olive oil" was seized in southern Italy. Here, too, the authorities discovered large quantities of oils and chlorophyll.

This list could probably go on forever.

Despite the measures taken by the authorities, the problems do not seem to be getting any less, as the following video summarizes once again.

So how can the situation be addressed?

Measures against food counterfeiting and food fraud

As a consumer, you probably have the simplest lever in your own hands by buying high-quality food from your trusted retailer, which then also has its price.A jar of honey or a bottle of olive oil for 2-3 euros simply cannot be of good quality.

If you have the opportunity to buy directly from the producer, this is of course often best. Otherwise, it makes sense to choose retailers who are transparent about the origin of their products and communicate this to the customer.

A reputable retailer naturally knows their purchasing sources, especially if they have been working together for years or decades, and of course also carries out analyses in order to be able to track the quality status of the products at all times.

As described above, the latest analytical methods should be used, in the case of honey DNA analysis.

In the case of olive oil, a rapid test was developed a few years ago by the North Bavarian NMR Center at the University of Bayreuth.

In this case, NMR stands for nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

This test was developed in collaboration between Prof. Dr. Stephan Schwarzinger at the University of Bayreuth, the University of Athens, the analytical laboratory ALNuMed GmbH, now part of FoodQS GmbH, and other players from the olive oil industry.

This test is based on over 1,000 olive oil samples with which future samples can be compared.

NMR spectroscopy also makes it possible to analyze and evaluate a wide range of different ingredients and concentrations within a very short time in order to analyze and detect their origin, degree of authenticity or adulteration and ingredients.

Adulteration can therefore be detected quickly. Food retailers now only have to have this test carried out regularly.

This test has also been in use for honey since 2015.

The authorities have of course not been idle in the meantime. Operation Opson has been carried out annually since 2011. This is coordinated by Europol and Interpol and covers a large number of countries inside and outside the EU.

During the last Operation Opson in 2024, a total of 22,000 tons of food were confiscated, including the 42 tons of alleged olive oil described above.

A total of almost 6,000 checks were carried out, with 11 of them being criminal.000 checks were carried out, during which 11 criminal networks were dismantled, 104 people were arrested and arrest warrants were issued for 184 people.

We can only hope that such actions will continue to be successful in the future in order to uncover food fraud on a large scale and that consumers will also become more and more aware of their responsibilities.